How The Media Lie: The British Stole $45 Trillion from India

Vice, Al Jazeera, and multiple Indian media sources have reported that Britain allegedly took $45 trillion from India during colonial times. This claim has subsequently been leveraged to criticise Britain, capitalism, or White people in general. But what's the source of this figure, and how accurate is it?

The origin of this calculation can be attributed to Utsa Patnaik, a Marxian economist who first made the claim in her 2017 essay “Revisiting the Drain', or Transfers from India to Britain in the Context of Global Diffusion of Capitalism”.

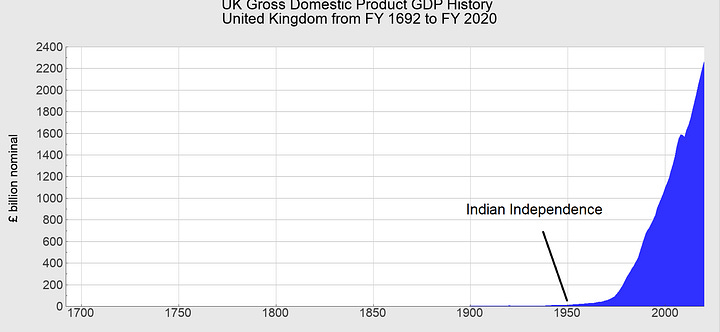

The presented $45 trillion figure purports to represent a "drain" on the Indian economy during the period from 1765 to 1938. Such an assertion is unfounded, considering that the total economic value within the Indian economy during that time frame never amounted to that extent. Furthermore, the $45 trillion does not delineate the actual nominal transfer from India, nor does it encompass the equivalent contemporary value when adjusted for inflation.

In its essence, the $45 trillion figure represents the outcome of a compounded interest investment calculated at a 5% interest rate, extending to the year 2016. When writing four years later for the Marxist magazine Monthly Review, Utsa recalculated the figure, extending the compounded interest rate to the year 2020 instead of 2016. In this four year period, Britain had stolen an extra $19 trillion, bringing the figure up to $64.82 trillion.

If we continue employing different temporal parameters using Utsa’s formula, we can find by 2050, Britain will have stolen $274.5 trillion. By the year 2080, Britain will have extracted a staggering $1.16 quadrillion. This demonstrates the absurdity of her figure.

Additionally, in her computations, she employs a historical conversion rate of one UK pound (£) to 4.84 US dollars ($). However, her analysis overlooks the significant devaluation of the UK pound (£) in 1949, accounting for a substantial 30% decrease in value against other currencies, and an additional 14% devaluation in 1967. These currency fluctuations merit careful consideration in order to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness in the calculations.

To highlight the flaws in Patnaik's approach, let's use her formula in a different context. Imagine if someone loaned you £1 in 1938; in 2023, you'd be owed $289.29. This amount is a staggering 13 times greater than the inflation rate.